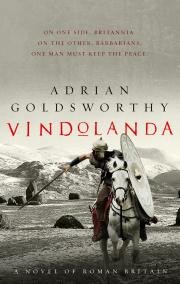

Roman Fiction

VINDOLANDA

Adrian Goldsworthy discusses the book.

Northern Britain in AD 98

We know very little about what was happening in the north of the Roman province of Britannia at the end of the first century AD, but the wider context was one of recent imperial retreat. Timbers for the first Roman fort at Carlisle were felled in AD 72 or 73. That means a long term presence in the north before the governor Cnaeus Julius Agricola arrived in 78 and embarked on a series of campaigns that would take him well into the north of Scotland and culminate in his defeat of a large Caledonian army at a place called Mons Graupius, the location of which is unknown. A legionary fortress was constructed at Inchtuthil in Perthshire, as well as numerous auxiliary forts and other installations, notably the line of watchtowers and outposts along the Gask ridge. All this suggests that the Romans planned to stay more or less permanently. Something then changed, prompting the abandonment of every base north of the Forth-Clyde line. There is no mention of any of this in our literary sources, which are very thin for these years and don't mention northern Britain at all. Coin evidence dates the withdrawal to AD 86-87. Sites like Inchtuthil were deliberately abandoned, being systematically demolished, and anything useful that was not carted away was burned or buried - the latter including thousands of iron nails. Given that a series of major wars developed on the Danubian frontier around this time, the best bet is that the Emperor Domitian took a legion and substantial numbers of auxiliaries because he needed troops for these conflicts. Reduced by at least a quarter, the garrison of Britannia was simply not big enough to hold all of the recent conquests in what would become Scotland.

The land between the estuary of the Solway and the mouth of the River Tyne offers the narrowest stretch of land south of the Forth-Clyde Line. Around 122 the Emperor Hadrian would order the construction of Hadrian's Wall here. So perhaps it should not surprise us that after the withdrawal from Scotland, the Romans occupied a line of bases in this area. There were garrisons to the north, notably Trimontium (modern Newstead) which figures in Vindolanda, but these look like outposts and something more like a concentration of troops was stationed on the Tyne-Solway line. In the past this has often been called the Stanegate frontier, after the Stanegate, the Roman road running west to east, and has been seen very much as the predecessor to Hadrian's Wall. Academic fashion inevitably changes, and this interpretation has been criticised and more recently championed again. (See for instance N. Hodson, 'The Stanegate: a frontier rehabilitated,' Britannia 31 (2000), pp. 11- 22). Some of the debate has more to do with disagreements over what a Roman frontier was and what it was intended to do more than any denial that there was something of a concentration of Roman bases in the area. That cannot be disputed, and ultimately it stretches credibility that this was mere chance, the forts established simply because the units had to be based somewhere.

The line of bases along the Stanegate were part of a wider network of forts further north and to the south that was felt to serve a useful purpose. The long-term focus on the area makes it clear that this purpose was seen important for much of the remaining three centuries of Roman occupation. We should note that the western section of Hadrian's Wall was originally built in turf and timber, using the fast and familiar methods employed by the army for constructing temporary camps. This probably means that it was constructed quickly, with speed being given priority over permanence, and hints at a serious threat in this area, presumably from some of the Novantae and Selgovae.

The reader will have noticed the repeated use of probably, possibly, perhaps etc. As I said at the start, very little is known about this area in this period. Most of what we do know comes from archaeology and here we face a big problem for a novelist trying to portray this part of the world in a specific year. Based sometimes on finds of coins, more often of a type of pottery, and deduction from levels on a site, archaeological dating can rarely be precise. We may say with confidence that something is Trajanic, perhaps even early Trajanic, but that means no more than within a decade or so. Trying to pin down what exactly was there in September 98 when our story starts is a good deal harder and often comes down to guesswork. We know that the forts at Corbridge, Vindolanda and Carlisle were there. So far no trace has been discovered of an army base east of Corbridge in this period. Carvoran or Magna was probably an 'early Trajanic' foundation and may not have existed in 98. I decided to include it, as it certainly appears to have been established very early in the second century. In the novel I have a clearly marked route running along the line of the Stanegate, but not yet the properly metalled Roman road. The Stanegate proper is Trajanic, and was probably constructed a few years after the turn of the century. The construction of small forts or fortlets at Haltwhistle Burn and Throp may well have coincided with the building of the road. These were both constructed in stone, making them probably the first stone walled army bases in the area, and provided inspiration for my fictional Syracuse, as a smaller and timber built predecessor. Newstead was abandoned c. 106 and perhaps this was part of a wider consolidation and reorganisation of the frontier zone. On the other hand we may be off by a few years or more in some or all of this dating which would make it less likely that they are linked.

The Vindolanda Tablets and the smaller collection from Carlisle show a strong military presence, as well as stable communities in and around the army bases, all part of the broader trade networks of the rest of the empire. Environmental evidence shows us that much of the land was deforested before the Romans arrived. Most of Hadrian's Wall seems to have been built on land already under plough, although there were exceptions, for instance at Birdoswald where the Romans cleared woodland before constructing the fort. Settlements of the indigenous, Iron Age peoples are even harder to date than Roman sites, and our uncertainty about many aspects of the Roman presence is as nothing compared to our understanding of the tribes of the area to whom we shall now turn.