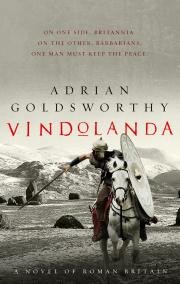

Roman Fiction

VINDOLANDA

Adrian Goldsworthy discusses the book.

What I didn't know

I have spent my adult life studying the ancient world, focusing most on the Romans and especially on the Roman army. Even before I went off to university, I read as much as I could find on the Romans. I am far from being alone in this obsession, but I have been very fortunate in being able to study the subject full time. Yet after more than a quarter of a century, there are many things that I do not know about Rome and its army. Every time I take on a new project I come across little snippets that I have either never read before or have forgotten. That's even without new ideas and new discoveries. Excavations throw up surprising results, new inscriptions or texts appear - for instance the recently published collection from London.

For all that, we still have to understand the ancient world on the basis of very little evidence. Only the tiniest fraction of ancient literature has survived into the modern world. The proportion of inscriptions on stone that have avoided destruction and have been found or may one day turn up is similarly minute. We are even worse off when it comes to the everyday 'paperwork' so common in Roman society and especially the highly bureaucratic army.

The more you study the ancient world, the more you realise how much we simply do not know. This can come as a surprise to the general public, who expect us to know far more. So often you get questions such as 'What colour were Roman army uniforms?' 'What was the shield device of this legion?' 'What drills did the army use?' etc, etc. When you answer 'well, we don't really know, but ... .' the reaction is sometimes to think that you personally do not know, but that's because you're not much good. It really is quite hard for many to accept that there is little or no evidence for many things. Having just written a non fiction book on Hadrian's Wall, and so dealt with a subject about which we know very, very little for certain, it's easy as a historian to forget that people do expect there to be hard and fast answers.

So we must begin with the admission that there are vast gaps in our evidence. To put it another way, trying to understand any aspect of the Roman world is like trying to put together a jigsaw where you only have at best 10% of the pieces and you do not know what the picture should look like. The Vindolanda tablets give us wonderful glimpses of life in the area at the time of the stories. However, our evidence for what went on during Trajan's reign in Roman Britain as a whole, let alone the north, consists of a few vague fragments. This gives a novelist a lot of freedom, since it essentially offers a blank canvas and as long as you don't do anything too wild - someone builds a railway or the British tribes rebel and throw off Roman rule forever - you can pretty much invent what you like.

Then there is a big difference between writing conventional history and a novel set in the same period. The historian not only can, but must admit when we do not know something or the evidence is poor. In contrast a character in a novel cannot open a door and find a blank space. In the months to come I'll talk more about the inspiration for the world of Vindolanda, but I drew ideas from a wide range of different cultures and periods, and sometimes made things up. When it came to the workings of the Roman army, I have tried out some ideas that could not be proved, but are possible interpretations of how it all worked.

In a novel you are concerned very much with the day to day and routine. Characters wear clothes (at least usually), eat and drink, sleep, sit, relax, work and live in particular places and in different ways. Much of this is the sort of thing you do not really think about as a historian working on Caesar, Cicero or the structures of the army and state. In this case, writing the novel threw up lots of questions. Sometimes there was no answer, because the evidence does not exist. Sometimes the evidence was there, but I had simply never thought of asking the question. In a story of this kind you have to deal with practicalities - just how would they do something. That raises an awful lot of good questions, and actually has forced me to look at the past in a different way.

Let's take one minor example. Flavius Ferox and the others spend quite a lot of time on horseback, but what sort of horses should they be riding? There is some skeletal evidence, which can be interpreted as the army preferring male horses. Some authors assert that the preference was for stallions. Yet the evidence is very limited. Sculpture does not make clear whether most animals were male or female, and the bone evidence is nowhere near clear enough to show that only male horses were used. One of the best commentators on the military use of horses by the Romans argues that while gelding was known, the risk of infection was very high, so that she doubts that this was used. The confidence and aggression of stallions could be seen as an asset during a battle. Yet if cavalry horses were intact, this makes you wonder about stabling arrangements, which in the current orthodoxy would mean keeping three stallions in a pretty small box for long periods of time. Added to that, battle - and indeed combat of any kind - was a comparatively rare experience, and even on campaign far more time was spent on patrol and escort duty, which raises questions about what were the most important characteristics looked for in cavalry mounts.

There are no easy answers to any of this. It began when I wondered whether I could have someone riding a mare because it is often convenient to be able to slip in the pronoun 'she' when you are otherwise writing mainly about male characters. (Those who have read Beat the drums slowly may remember the mare Bobbie, who grew into a bigger and bigger character as the story developed. She was actually based on a gelding called Richard, who had only one eye, some rather insanitary habits, and an uncomfortable jerking canter, but the appeal of being able to call the horse 'she' forced a sex change). On balance, I reckon the evidence leaves the whole question pretty open, and I have let the soldiers in Vindolanda ride stallions, geldings and mares. I have also depicted the turmae of troops of one unit, the ala Petriana ride horses of uniform colours, a practice common in eighteenth and nineteenth century armies, but not attested for the Romans. As a historian I cannot prove either of these things, but reckon that the first is quite likely and the second idea at least possible.