Roman Fiction

VINDOLANDA

Adrian Goldsworthy discusses the book.

Vindolanda - the place

Vindolanda - modern Chesterholm - lies a few miles south of the line of Hadrian's Wall, but the first Roman fort on the site pre-dates the Wall by more than a generation. Five successive timber forts were constructed on the site, the earliest probably dating to sometime around AD 90. The novel is set at the time of the third timber fort, much of which lies under later stone buildings and has yet to be explored. The earliest forts pre-date the construction of a proper Roman road, known to us as the Stanegate from its Anglo-Saxon name, but it looks as if this largely followed the route of an earlier more basic route employed by the army, which passes close by Vindolanda.

In later years the timber forts would be replaced by a series of stone forts. Even though it lies behind the line of the Wall, Vindolanda appears to have been occupied throughout the existence of Hadrian's Wall and formed part of the wider frontier system. R. Birley, Vindolanda. A Roman frontier fort on Hadrian's Wall (2009) is an excellent and detailed overview by author who led the excavations for many years.

Vindolanda is just one of many known sites of Roman forts laid out to accommodate a unit of auxiliary troops - the non citizen soldiers who made up more than half of the Roman army. It is an atmospheric spot, but what it makes it special is that local conditions have preserved many artefacts which do not normally survive. This means that the on-going excavation at the site continues to uncover objects of a quantity and quality rarely matched. More Roman-period shoes have been found at Vindolanda than anywhere else in the empire. The total is now well over five thousand shoes or fragments of shoes and the number continues to grow with each new season of excavation. Other leather objects, including numerous fragments of army tents, along with objects in wood and other natural products, are common. Many are displayed in the museum on site and in the nearby Roman Army Museum at Carvoran, the site of another auxiliary fort. Both are well worth a visit and details can be found on the Vindolanda Charitable Trust's website - http://www.vindolanda.com/

Simply with this material Vindolanda would be special, but the discovery there of hundreds of wooden writing tablets dating to the era of the wooden forts makes the place truly inspiring. Painstakingly deciphered, these texts are often mundane, and it is their everyday quality that brings to life the community living in and around the fort at the turn of the first-second centuries AD. The novel was inspired by the famous birthday invitation from the wife of another garrison commander to the prefect's wife at Vindolanda. There are military documents, strength reports, assignment of soldiers to tasks, daily reports, applications for leave, letters of recommendation, lists of purchases and items sold, and many tantalising fragments difficult or impossible to categorise. In published form these are available as A.K. Bowman & J. D. Thomans (eds.), The Vindolanda Writing Tablets (Tabulae Vindolandenses) Vol. II (1994) and Vol III (2003). Many are already available on-line at http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk/index.shtml

Some are intriguing, such as 164, the famous Brittunculi document, the word presumably a diminutive and disparaging nickname for the locals:-

"... the Britons are unprotected by armour (?). There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons mount in order to throw javelins." -

The fragment is brief and its context unknown. It might be a report describing the fighting practices of locals - presumably at least potentially hostile locals - intended for a new officer or even commander. Another suggestion is that the information was to inform Roman officials eager to recruit locals for the army, perhaps as an irregular unit or numerus. We simply do not know, for all we have is this little fragment and as the reconstruction of the text involves a good deal of deduction. This is often the way with the tablets. I have taken names and some incidents from them to create the world of the novel. These have been supplemented by similar documents on writing tablet, papyrus or pottery ostraka from other provinces.

Like the writing-tablets, these tend to deal with the everyday and routine. There are only a few glimpses of possible disturbances and the threat or reality of violence, but that is not surprising. Day-to-day paperwork even at times of a major crisis consists overwhelmingly of dull, routine material.

The archive associated with Flavius Cerialis, and supplemented by the documents connected with his wife Sulpicia Lepidina, is the largest associated with any individual. Many of the letters written by him most likely represent drafts rather than the fair copy actually sent, but there are also accounts and correspondence sent to him by other senior officers and a range of individuals, some of whom may well be civilians. Judging from the surviving texts, Aelius Brocchus and his wife Claudia Severa were frequent correspondents and presumably friends, visiting each other reasonably often. Cerialis commanded cohors VIIII Batavorum during the third phase of the timber fort. I have stretched this period a little to include AD 98, but it is now dated to have begun sometime c.100. It is not clear when he arrived to take command of the cohort or how many years he spent there. His name suggests very strongly that, like the men he commanded, he was a Batavian and that either he, or his father had been granted Roman citizenship during the Batavian Revolt of AD 70. Tablet 628 was written by a decurion named Masclus or Masculus who refers to Cerialis as his king (regi suo). Unless this is mere sycophancy, this raises the possibility that Cerialis belonged to a family considered to be royal by the tribe.

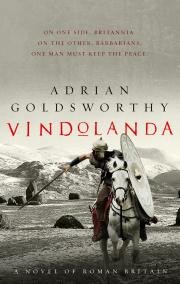

A historian may well be cautious about making such a firm conclusion, but as novelist I have had no hesitation in writing of him in this way. The tablets give us no indication of Cerialis' age, appearance, or past career. His wife is an even more shadowy figure, allowing me to invent stories for each of them. The cohort left Vindolanda by around AD 106, and if they had not already left, Cerialis and his wife went with them. We know nothing of what happened to either of them subsequently, and all we have are these little glimpses into their lives during the time spent at the fort. Part of their house, the praetorium, has been excavated, uncovering in the main working and storage rooms. In the novel almost all the details of the building are invented, as is the idea that it had two stories. In later periods, the stone houses built for auxiliary prefects invariably had their own private bath houses. We do not know what bathing facilities were common in their timber predecessors. The first stone bath house outside Vindolanda (shown on the far right of the Peter Connolly illustration on the book's front and end pieces) was not completed until late in the life of the third fort, c. AD 105-106. Bathing was so important in Roman society that I have assumed that some basic facilities would have been considered desirable, even when the full panoply of furnaces and heated floors and walls was clearly impractical and unsafe in a timber building. Like so many other details, this is something I had never really considered until I came to write the novel.